Feature Article in American Association of Legal Nurse Consultants The Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting LNC Work Products

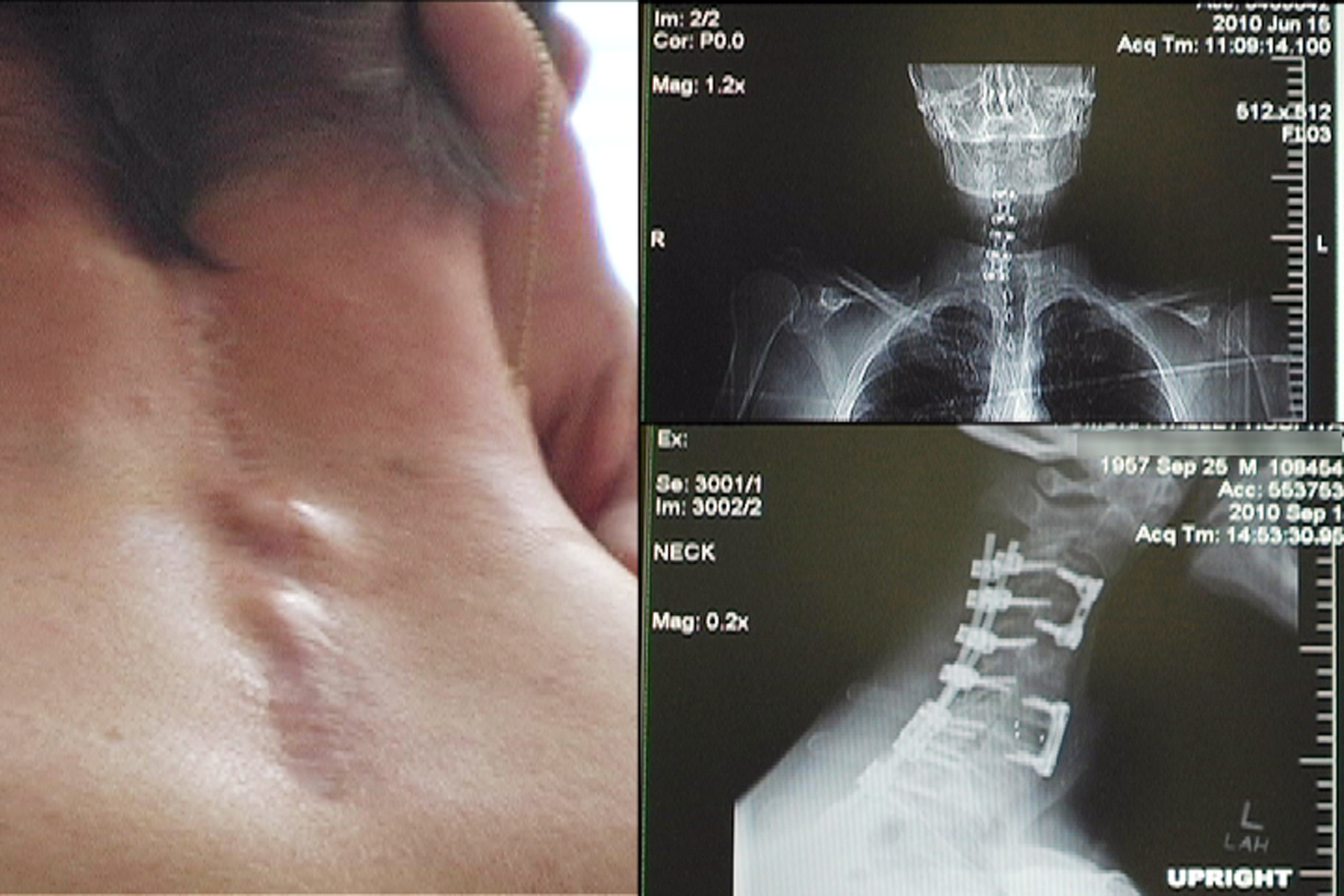

A plaintiff who is permanently, or catastrophically injured needs to have the harm they have suffered told in an effective and convincing manner. How a story is presented to a jury, or mediator is critical for the way their damages are assessed and awarded. In most cases, using mere words to express the loss a plaintiff has suffered does not compare to actually watching them as they adapt to a new life full of physical limitations and challenges. If seeing is believing, and a picture is worth a thousand words, a day-in-the-video is worth its weight in gold.

When it comes to all personal injury matters, the plaintiff’s lawyer must first prove opposing parties liable, then present the respective damages for his, or her client. Liability is sometimes more evident in some cases than others, but we all know attempting to communicate and assess the value of the plaintiff’s injuries is no easy task. This is especially true if jurors have had no exposure to a catastrophically injured person. Trying to explain what a quadriplegic’s day is like is nearly impossible. But just as demonstrations of injuries in-court are permissible, so too are activity of daily living, or day-in-the-life videos.

Day-in-the-life-videos are typically presented in court to demonstrate for jurors a plaintiff’s injuries (permanent and/ or catastrophic), and the impact those injuries have on the plaintiff’s daily living activities. Carefully videotaped footage of these activities — such as rising, feeding, bathing, toileting, and receiving physical, speech, and occupational therapy — can vividly demonstrate the plaintiff’s dependency, limitations, and frustrations – better than words could ever do. Whether the plaintiff is managing life on their own, has a caretaker, or is living in a care facility, a day-in-the-life-video can effectively communicate what the client’s life is like living as they struggle with completely ordinary daily tasks with a permanent personal injury.

BETTER THAN WORDS

The videotaped footage is intended to bring jurors inside the plaintiff’s life in a way that is virtually impossible to communicate, and circumvents the impracticality of having jurors visit the plaintiff themselves to witness the plaintiff’s injuries and challenges firsthand, especially if the plaintiff is homebound, or cannot not perform certain tasks for demonstration in-court. For this reason, day-in-the-life video presentations are powerful tools for personal injury cases, and the courts wholeheartedly agree.

In Grimes v. Employers Mutual Liability Insurance Company of Wisconsin, (D.Alaska 1977) 73 F.R.D. 607, 610, the court found the day-in-the-life video submitted by the plaintiff exemplified “better than words,” the impact the injury had on the plaintiff’s life in terms of pain and suffering and loss of enjoyment of life.

In Grimes v. Employers Mutual Liability Insurance Company of Wisconsin, (D.Alaska 1977) 73 F.R.D. 607, 610, the court found the day-in-the-life video submitted by the plaintiff exemplified “better than words,” the impact the injury had on the plaintiff’s life in terms of pain and suffering and loss of enjoyment of life.

Similarly, in Arnold v. Burlington Northern Railroad (Or.Ct.App. 1988) 748 P.2d 174, 176, the court noted that although the video offered to illustrate and supplement the plaintiff as cumulative testimony, “the day-in-the-life film communicated to the jury effectively, and perhaps better than words could do; what plaintiff’s life…was like.” [Italics added].

Also, in the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, Bannister v. Town of Noble, (U.S.Ct.App. 1987) 812 F.2d 1269, the court surmised that “a jury will better remember, and thus give greater weight to evidence presented in a film as opposed to more conventionally elicited testimony.”

TRIAL ADMISSIBILITY GUIDELINES

In recognizing the power of the medium of moving pictures, courts have established that day-in-the-life videos must conform to the same rules as any other forms of demonstrative evidence. Meaning their admissibility is subject to broad, although not absolute, judicial discretion and the party submitting the video must provide the appropriate legal foundation for its admission into evidence. Most courts will admit such day in the life videos provided that (1) their probative value outweighs any prejudice to the defendant, Arnold v. Burlington Northern Railroad (Or.Ct.App. 1988) 748 P.2d 174, 176 and (2) there are no demonstrated improprieties in the video’s content or production techniques, Ocasio v. Amtrak, (N.J. Super. App. Div. 1997) 690 A.2d 299.

The party proffering the video as evidence must show that the videotape is an accurate portrayal of the events depicted, Cisarik v Palos Community Hospital (Ill.1991) 579 N.E.2d 873, 875. Someone who has personal knowledge of the videotape’s contents and must be available for in-court cross-examination to lay foundation: typically the plaintiff, a caregiver, nurse practitioner, or the person most knowledgeable from the video production company.

In order to be representational, day-in-the-life-videos must have a foundation of accuracy and fairness, Foster v. Crawford Shipping Company (3d Cir. 1974) 496 F.2d 788, 790. For instance, the scenes depicted in the video may be unpleasant, but its prejudicial impact cannot substantially outweigh the video’s probative value. If the video does not present probative value it may not be admitted into evidence.

The plaintiff’s counsel must show that the daily activities in the video were typical for the plaintiff, so that the admission of the video would not be unduly prejudicial, Cisarik v Palos Community Hospital (Ill.1991) 579 N.E.2d 873, 875. Nor should the day-in-the-life-video contain inter alia, artistic highlighting that emphasizes some scenes more than others, obvious exaggerations, self-serving behavior by the subject/plaintiff(s), scenes that serve mainly to create sympathy, or those that contain other unduly inflammatory material.

DOCUMENTING PLAINTIFF’S DAILY ACTIVITIES

Because a day-in-the life video must follow the Rules of Evidence, it needs to be filmed and edited in a precise way. It is best to commission an experienced legal video production company that understands the common admissibility requirements and has a track record of having their work admitted at trial.

Firstly, if the plaintiff is receiving care from a nursing or rehabilitation facility, the attorney must receive permission to film at that location. The videographer must be very careful not to film other patients at the facility. Should someone be inadvertently videotaped, that person’s face must be blurred during the post production, or editing process. The same goes for any nudity that may be captured during changing or shower scenes; those scenes must be blurred as well out of respect for the plaintiff, and members of the jury.

Secondly, the videographer should approach the taping as an unbiased third-party and merely document what the plaintiff’s typical day is like. It is helpful for the videographer to know what the sequence of the events will be, but at no time should they direct, or dictate the plaintiff’s actions in-camera. The videographer should never ask the plaintiff to do anything out of the ordinary – remember for admissibility purposes, they should only document a typical day.

The most critical time of the day is usually when the plaintiff performs their morning activities, or receiving morning care. It is important the videographer arrive prior to the plaintiff’s typical rising time and begin filming prior to any care takes place. During filing colloquy should be kept to an absolute minimum, with the videographer recording the ambient sound.

Most day-in-the-life videos can be videotaped in 4-hours. However, if a plaintiff is residing in a rehabilitation facility, physical, occupational and other therapies are likely scheduled throughout the day, therefore lasting more than 4-hours. With 4 to 8-hours of footage captured, the video then needs to be edited to a reasonable timeframe. A good goal is to have all of the footage whittled down to about 12 minutes in order to keep jurors’ attention.

The editing process can be a vexing one, in that there is a delicate balance of what is shown in the final cut and what does not. For instance, a jury does not need to watch the entire process of a plaintiff needing to be digitally stimulated for a bowel movement when only a thirty seconds to 1 minute will do to get the point across.

At trial, the video will be played while the person best suited to authenticate the video is on the stand. That person, usually someone who was present during the filming, may be asked to narrate for the jury the actions being performed on-screen, Cisarik, supra.

FOR PERMANENT INJURY CASES

One misnomer about day-in-the-life videos is they are reserved for catastrophic injury victims only. Certainly your average juror has not been exposed to the daily activities of a person suffering with quadriplegia, or a quadrilateral amputation, but nearly any permanent injury can be documented and presented with a lasting impression at trial. Keep in mind this is all about assessing how the plaintiff has been harmed so the jury can award the proper damages. If seeing is believing, and a picture is worth a thousand words, then a day-in-the-life video is worth its weight in gold.

One misnomer about day-in-the-life videos is they are reserved for catastrophic injury victims only. Certainly your average juror has not been exposed to the daily activities of a person suffering with quadriplegia, or a quadrilateral amputation, but nearly any permanent injury can be documented and presented with a lasting impression at trial. Keep in mind this is all about assessing how the plaintiff has been harmed so the jury can award the proper damages. If seeing is believing, and a picture is worth a thousand words, then a day-in-the-life video is worth its weight in gold.

Although there is no absolute measure for how a day-in-the-life video impacts the plaintiff’s bottom line, I personally have been involved in matters where the jury has awarded significant sums after watching the day-in-the-life videos. A case involving a 13-year old boy who was paralyzed from the chest down after being shot by Los Angeles Police Department was awarded $24 million, Rubin, Joel. “LAPD ordered to pay $24 million in shooting.” Los Angeles Times, January 19, 2016: Home Edition Main News Part A Page 4. A teenage plaintiff was rendered paraplegic after being involved in a car accident with a defective seat belt was awarded $12.5 million Hirsch, Jerry. “Jury says Toyota must pay reality TV star $12 million for crash injury.” Los Angeles Times, October 21, 2014: latimes.com. A medical malpractice matter involving a 27-year old who went into septic shock at a hospital and had all 4 limbs amputated as a result, was awarded $13.3 million, “$13.3 Million Settlement Medical Malpractice-Quadrilateral Amputation .” March 2015: www.conaldoylelaw.com/About/Landmark-Cases during the arbitration process after the video was played.

Although the cases mentioned above may not be typical, they make the case for the effectiveness of presenting a plaintiff’s injuries to the opposing side as evidence of the harm they have caused. In short, day-in-the-life videos can be effective, and should be admissible at trial as demonstrative evidence as long as they do not contain, inter alia, artistic highlighting, obvious exaggerations, self-serving behavior, scenes which serve little purpose other than to create sympathy or contain other unduly inflammatory material.

To view a day-in-the-life sample video, visit: Verdict Videos Day-in-the-Life

Kelly Deutsch is a four-time, award-winning executive producer who brings her unique legal background and television production know-how to Verdict Videos. With over twelve years’ experience as a television writer, producer and director. As an accomplished production manager of courtroom trial presentations and legal video documentaries, Kelly became captivated by the importance of story-telling in the courtroom. Kelly’s analytical approach, combined with her visual storytelling skills allows her to extract “the real story” from plaintiffs in a fashion which is second to none. Her deep compassion and empathy for each individual’s suffering can be seen and felt with every production. She may be contacted at Kelly@verdictvideos.com